| |

|

I love this part

of Suffolk. The area west of Halesworth is one of the

most rural parts of East Anglia, and Chediston is one of

its least known villages. It is always a pleasure as the

days lengthen in early spring to get back in the saddle,

cycling around the parishes I had originally visited for

the Suffolk Churches site back in the 1990s, and which I

have enjoyed revisiting a number of times since.

As on the last occasion I came down the long lane from

Wissett, up over the ridge and then dipping down into

Chediston, the church tower appearing for the first time

on the rise ahead. The site suggests ancient origins.

Small houses bound the churchyard on all sides, and the

track to some of them actually goes through the

churchyard. There is an intensity to the church's

integration into its village, and so many rural English

churches must have had settings like this once.

The sparsely elaborated tower and cemented walls of the

nave and chancel make the church feel at first a bit

austere, especially if you've just come from one of the

pretty round-towered churches in this area. In fact, the

base of the tower is 13th century and the top was rebuilt

towards the end of the 15th century, but the unbuttressed

sides still seem more primitive than those of some of its

contemporaries. There is some evidence of Norman work in

the nave walls, but the overwhelming feeling inside is of

Suffolk's typically late medieval architecture. With one

important exception, the nave windows are set with clear,

19th century quarries, and so this part of the church is

full of light. The fine East Anglian font is in excellent

condition, its lions and woodwoses standing proudly. It

is very like the one over the ridge at Wissett, and they

may well have been carved by the same hand.

When the church was restored in the 1890s, the head of a

large St Christopher was revealed by the removal of some

plaster. Interestingly, one of the windows had been

punched through him before this exposure happened. This

is interesting, because the window was probably inserted

in the 15th century. This suggests, as elsewhere, that

wall paintings were not victims of the Reformation, but

were in many places covered over perhaps a century

earlier. The Victorian restoration here was roughly

contemporary with the lunatic restoration at nearby

Cookley, from which the beautiful pulpit here was

rescued. It has a grand stairway, with the date 1631 on

it. Mortlock observed that it was probably produced by

the same person as that at Rumburgh.

The nave has two striking furnishings, each of which is

worth a visit on its own. The first is the war memorial

window of 1949 by Margaret Edith Rope. It depicts St

George and St Felix, and if the figures seem a little

doll-like then that was her intention. They stand above

the arms of the RAF Bomber Squadron and the seal of the

Borough of Dunwich, for there is a persistent belief,

without any evidence, that Felix's see, Dummoc, had been

at Dunwich. The loveliest feature of the window is that

it contains rural Suffolk scenes in the background,

ploughing behind St George and harvesting behind St

Felix.

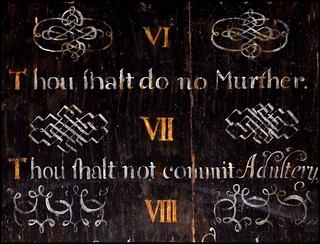

East Anglia has a

number of surviving decalogue boards from the 17th

century, and Chediston's is probably the best. Moses and

Aaron flank the Ten Commandments from the Book of Exodus.

They both look very serious. Moses wears his horns of

light, while Aaron wears what might be taken as either

eucharistic vestments or masonic regalia. The sixth

commandment exhorts us to do no Murther, while

the seventh presents Adultery in a flowery

script, as if to subliminally suggest its potentially

attractive possibilities.

The chancel, is home to Chediston's remarkable early 17th

Century communion rails, acorns suspended above spikes

that look as if they might impale the fruits as they

fall. They are properly Laudian, designed to guard the

altar and keep out dogs. The Puritans hated this kind of

thing, perceiving that the manner in which they cordoned

off the sanctuary was an attempt by a movement within the

Church of England to take the nation back to Popery. They

are exactly the kind of thing that led to the English

Civil War, a strange thought.

Revisiting so many churches over several decades I find

something reassuring about finding how little has changed

in them when I know how much has changed in my own life.

There is a danger in this creating a kind of vicarious

nostalgia, for I am increasingly conscious of the gentle

ripples caused by the Church of England as it pushes

itself in new directions, reinventing itself for changing

communities, reborn or transformed or, at a small number

of churches, beginning to die.

What I felt revisiting Chediston was something steadfast,

a sense of confidence rooted, not so much in theology,

but in being a touchstone to the village and its people

down the long generations, past and present, and

intending to still be there for the future, too.

Simon Knott, April 2019

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

|

|

|