| |

|

Combs,

pronounced to rhyme with looms, is a

large parish, and although there is a remote,

pretty village that takes its name up in the

hills, the bulk of the population of the parish

is down in the housing estate of Combs Ford in

suburban Stowmarket. Consequently, this church is

often busy with baptisms and weddings, and can

reckon on a goodly number of the faithful on a

Sunday morning.

St Mary is on the edge of the housing estate, but

the setting is otherwise profoundly rural: you

reach it along a doglegging lane from the top of

Poplar Hill, and the last few hundred yards is

along a narrow track which ends in the wide

graveyard. The church is set on low ground, hills

rising away to north and south, and the effect,

on looking down at it, is of a great ship at rest

in harbour.

With its grand tower, aisles and clerestories

this is a perfect example of a 15th Century

Suffolk church in all its glory. In the 1930s,

Cautley found the main entrance through the south

porch, a grand red brick affair of the late 15th

century. It has since been bricked up, and

entrance is through the smaller north porch,

which faces the estate. The gloom of the north

porch leads you into a tall, wide open space,

full of light, as if the morning had followed you

in from outside. If you had been here ten years

ago, the first striking sight would have been the

three great bells on the floor at the west end.

They represented the late medieval and early

modern work of three of East Anglia's great

bell-founding families, the Brayers of Norwich

and the Graye and Darbie families of Ipswich. The

largest dates from the mid-15th century, and was

cast by Richard Brayser. Its inscription invokes

the prayers of St John the Baptist. The other two

come from either side of the 17th century

Commonwealth; that by Miles Graye would have been

a sonorous accompaniement to Laudian piety, while

John Darbie's would have rung in the Restoration.

It was fascinating to be able to see them at such

close quarters, but they have now been rehung in

the tower.

Stretching eastwards is the range of 15th century

benches with their predominantly animal bench

ends, some 19th Century but mostly medieval in

origin, albeit heartily restored and even

replaced by the Victorians. The effect is similar

to that at Woolpit a few miles to the west. The

hares seem alert and wary, as though they might

bolt at any moment. Clearly, the medieval artist

had seen a hare, but lions were creatures of his

imagination.

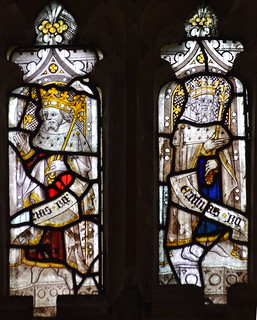

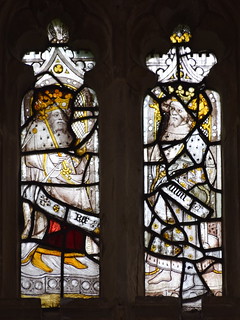

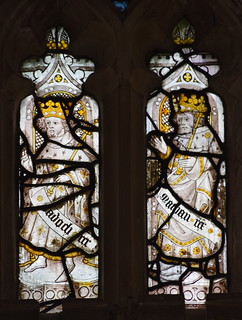

The great

glory of this church, however, is the range of

15th century glass towards the east end of the

south aisle. It was collected together in this

corner of the church after the factory explosion

that wrecked most of Stowmarket and killed 28

people in August 1871. The east window and most

easterly south window contain figures from a Tree

of Jesse, a family tree of Christ. Old Testament

prophets and patriarchs mix with kings, most of

them clearly labelled: Abraham and his son Isaac

wait patiently near the top, and Solomon and

David are also close companions.

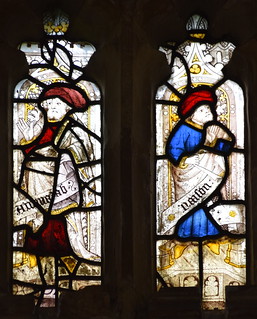

This second window also contains two surviving

scenes from the Seven Works of Mercy, 'give food

to the hungry' and 'give water to the thirsty'.

But the most remarkable glass here consists of

scenes from the life and martyrdom of St

Margaret. We see her receiving God's blessing as

she tends her sheep (who graze on, apparently

unconcerned). We see her tortured while chained

to the castle wall. We see her about to be boiled

in oil, and most effectively in a composite scene

at once being eaten by a dragon and escaping from

it. Because there is so much 15th Century glass

at Combs, I have organised the panels here window

by window, bearing in mind that all this glass is

reset and is not in its original place in the

church. Hovering over the image should produce a

description, and there's more information when

you click through.

south

aisle, second window from the east:

south

aisle, first window from the east:

south

aisle, east window:

glass

elsewhere in the church:

Under the vast chancel arch

is the surviving dado of the late 14th/early 15th

Century roodscreen, a substantial structure

carved and studded with ogee arches beneath

trefoiled tracery, the carvings in the spandrels

gilded. At the other end of the church, the font

is imposing in the cleared space of the west end.

It is contemporary with the roodscreen, and the

suggestion is that we are seeing a building that

is not far off being all of a piece: the fixtures

and fittings of a new building roughly a century

before the Reformation.

A period of history not otherwise much

represented here is that of the early Stuarts,

but a brass inscription of 1624 reset on a wall

had echoes of Shakespeare: Fare well, deare

wife, since thou art now absent from mortalls

sight. One of those moments when the human

experience transcends the religious tussles of

those days.

Outside in the graveyard, two other memorials

caught my eye. One dates from 1931, and remembers

My Beloved Sweetheart Stan... who died in

Aden aged 22 years. Not far off, a small

headstone of the late 17th Century records that Here

Restesth ye body of Mary, ye wife of Tho. Love

Coroner with two still born Children. I

stood in the quiet of the graveyard, looking

across to the suburbs of the busy town of

Stowmarket, and I felt the heartbeat, the

connection down the long Combs Ford centuries.

Behind me, there was something rather curious.

Although this is a big graveyard, the church is

set hard against the western edge of it. Because

of this, a processional way was built through the

base of the tower by the original builders, as at

Ipswich St Lawrence and Stanton St John. This

would have allowed medieval processions to

circumnavigate the church on consecrated ground.

The way here has since been blocked in, and is

used as storage space. A surviving stoup inside

shows that, through this processional way, the

west door was the main entrance to the church in

medieval times, when this building was the still

point of the people's turning world.

|

|

|