| |

I've been here a good many

times, but one visit stands out in my mind. I

remember that it was a spring day, back in 2006.

I had left Woolpit, and was cycling out into the

hills. Woolpit is a fine village, with pubs and

shops and fine old houses, as well as one of

Suffolk's most interesting churches, despite its

faintly ridiculous 19th century steeple. The

village is smaller than you'd expect from its

centre, and soon I was threading through narrow

lanes that dog-legged and climbed beside open

fields.

Not long after leaving the houses behind I

entered Drinkstone parish, and here side by side

were two windmills, both now without sails but

majestic still in the early spring sunshine. They

are particularly interesting because the 16th

Century post mill is the oldest in Suffolk. The

smock mill beside it is not much younger,

although it has been successively rebuilt over

the years. Both were still in use into the 20th

Century.

The sky clouded suddenly, and then there was the

most tremendous thunderstorm. Soaked to the skin,

I came down the hill into the village of

Drinkstone. The infant River Blackbourn runs

alongside the village street, and you cross it

and climb up to All Saints. The rain stopped, the

sun came out and the setting was lovely, the

church above the road on a soft cushion of green,

the old school beside it.

It might surprise you learn that the tower is

neither medieval or Victorian. It was one of the

earliest Suffolk towers built specifically to

accommodate recreational bell-ringing, dating as

it does from the last years of the 17th century,

when this sport was beginning to take off. We

know it was built at the behest of the Rector

Thomas Cambourne, who also paid for the bells. A

plaque remembering this is set in the west wall

of the tower.

It is interesting to compare Drinkstone's tower

with earlier Tudor red-brick towers like Hemley

and Charsfield, and later 18th century ones ones

like Grundisburgh and Cowlinge. It has more in

common with the former than the latter, except

that here there are classical louvred arches,

perfectly designed for the bells to sound out

from. If it looks more medieval than it is then

it may be because of the lancet in the base

stage, part of an 1860s upgrading by Edward

Hakewill, whose trademark, a quatrefoil

clerestory, is also in evidence above the aisles,

looking very like the same thing at his Thurston

across the A14. He appears to have raised the

nave roof, or at least the angle at which it cuts

into the tower, because this now looks rather

awkward. If so, the east wall of the nave must

also be his. The tracery in the east window

certainly is, and that whole face of the chancel

has been rebuilt. The 1860s glass in the east

window is by Lavers & Barraud. |

I find it hard to warm

to Hakewill's work. His introduction of high gloom into

the churches he restored seems intentional, and is often

coupled with low aisles that only increase the austerity.

Luckily, the great aisles here make the nave as wide as

it is long, and you step in to a feeling of lightness.

The great tower arch contains a modern ringing chamber in

light wood, which looks splendid, and suggests that

Cambourne's work is still very much appreciated.

One of the best things about this church is its

scattering of 14th and 15th Century glass, Some of which

is unusual, but all of it quite heavily restored. In the

upper lights of the south chancel window are angels of

the Precious Blood swinging censers. Christ in Majesty is

at the top, and the two figures either side are two Marys

and St John, reset here from a rood group.

The font is set

against a pillar in the south arcade in the traditional

manner, and is one of those arcaded octagonal fonts you

find mainly in the east of the county, usually made from

Purbeck marble. Or, at least, it appears to be, but I

couldn't help wondering if it was actually an older,

square font that had been cut down and decorated by

someone locally. It just doesn't have the same finish as

other fonts in this style. The benches are Victorian, and

there are some hefty bench end carvings. Mortlock thought

they might be from the studio of the great Ipswich

woodcarver Henry Ringham, whose work is much in evidence

up the road in Woolpit, but I wasn't so sure. They don't

seem to me to be of the usual delicacy of his work. The

dove with an olive branch, for example, looks more like a

chicken.

There are also a couple of medieval bench ends at the

back, and they repay more than a passing glance. Although

the bench ends are very badly damaged, they both have

carvings on them. One is an angel who has had his front

neatly sliced off, presumably by an iconoclast to

eradicate the design on his shield, while the other is a

version of the carving at Blythburgh which is often

referred to as 'scandal' - a face carved into the

poppyhead with an outstretched tongue.There is another

near here at Bradfield St George. This version is rather

more elaborate than those two, because there are two

further heads sticking out their tongues to left and

right beneath the top head, and they have not been

vandalised like he has.

Despite being repainted, the roodscreen is beautiful, the

upper tracery boiling like lace into the air. The

roodloft stairway set in the north wall beside it is one

of the most complete in Suffolk, retaining all its

original steps and even the handrail. There is a very

curious stone platform stretching west of here. Today it

is used for the lectern, but it may have been part of a

tombchest originally, or even what Mortlock calls a

preaching platform. It is certainly very unusual.

The drop-sill sedilia in the sanctuary has lost its

arching, but the wooden panelling set into the back of it

is medieval. Perhaps it came from the roodloft here. It

was probably set there during the 19th century

restoration, and may have come from anywhere originally,

I suppose.

The family at Drinkstone Hall for many years were the

Grigbys, and they've left their mark here. Two matching,

elegant 18th century memorials with urns on flank the

vestry door, with a simpler one above.

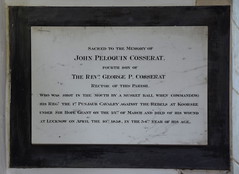

But more interesting are

two memorials, one in the nave, the other on the

north side of the chancel. Thomas Grigby was

killed in the Peninsula war of 1811 - on

board a transport bound for Cadiz, he was run

down by the Franchise frigate off Falmouth and

perished together with 233 souls. Almost

forty years later, during the Indian Mutiny,

fourth son of the Rector John Peloquin Cosserat

was shot in the mouth by a musket ball while

commanding his regiment the first Punjaub Cavalry

against the rebels at Koorsee, an incident

which seems to have stepped out of the pages of The

Siege of Krishnapur.

As you can

see, All Saints is full of interest. It doesn't

wear its heart on its sleeve, and there must be

very few of the many hundreds who visit Woolpit

every year who ever make it down the road to

here. I wandered around the graveyard in the

sunshine. Although the area to the west of the

tower has been partly cleared, the rest is fun to

explore, with lots of 19th century graves and

even some 18th century survivals. The massive yew

tree by the south porch must have seen a fair few

funeral processions in its time. I wandered

further eastwards, and, as I approached it, one

of the largest cats I've ever seen bestirred

itself lazily from the long grass and wandered

off. I guess there must be rich pickings for a

hunting cat in a place like this.

And there are riches for church explorers in this

area, many of them as little known as Drinkstone.

The next parishes in each direction are Gedding,

Rattlesden, and the wonderful Hessett, all worth

an hour of your time, all as open and welcoming

as this one.

|

Simon Knott, October 2019

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

|

|