| |

|

|

|

This is a tale of

two visits, one in the depths of winter,

the other on a fine day in high summer

twelve years later. I can tell you now

that on neither occasion did I get inside

this church, so if that is all you are

interested in you may as well stop

reading now.

The occasion of my first visit to Little

Cornard church was on Boxing Day 2000. It

was one of those chilly, damp winter days

when the temperature plummets towards

zero, forgets to stop, and heads below.

That evening, a group of us sat in the

fierce, dark, convivial heat of the Ship

and Star in Sudbury, escaping from the

bosom of our families, and getting

quietly mellow.

This had become something of a tradition

for us; and, it would seem, for other

people too, for the place was heaving. My

friend Stephen (all locals will know his

house on Acton Square, the one with

lifesize Star Wars characters standing in

the windows) was holding court.

Jacqueline discovered a group of old

school friends, and ensconced herself in

a round with them; I was pinned in a

corner with Sarah, who daily commits the

sheer act of lunacy of commuting from

Sudbury to Martlesham, Catherine who

works in a Seventies retro-clothes shop

in Dublin (no, she doesn't commute) and

Nancy, who actually comes from Little

Cornard. |

I had bumped into Nancy and

her mother earlier in the day, on the wild track

that leads through a farmyard along the ridge to

All Saints; but it had been so cold, so bitterly

cruel, and we had all wrapped ourselves up beyond

recognition; so it was only on reflection that

we'd realised who each of us were. And now, my

mind kept going back to that beautiful, secret

place; for the graveyard of All Saints is quite

simply one of the loveliest places in all

Suffolk. As Mr Adnam worked his magic, my

thoughts drifted gently through the icy silence

of the tree-wreathed graves, and the sweet little

church itself.

Anyone who knows Great Cornard, that vast 1960s

estate on the south side of Sudbury, would not

begin to think that its twin in name only could

be so totally different. If anyone knows anything

of Little Cornard, it is probably Martin Shaw's

hymn tune of that name, the most common setting

of Hills of the North Rejoice. So on

Boxing Day morning, we abandoned our children

with their grandparents, and set out to find it.

You leave the centre of Sudbury on the Bures

road, through the light industry and large

Victorian houses, past mundane St Andrew and the

pubs, the roofs of acre after acre of lowrise

council estates below you. After a couple of

miles, the houses thin out, fields appear, a pub

that is very much a village one passes, and you

are in Little Cornard. As you reach the real

countryside, a sign directs you up a steep lane

to the left, and your adventures begin.

The narrow lane climbs steeply between high

hedges, and you hope that you don't meet anything

coming the other way. Soon, you reach the top of

a ridge above the Stour; it is actually the last

dying gasp of the Chilterns as they sink slowly

into the east. The road winds between 18th

century houses and 19th century farm cottages,

doglegging alarmingly at one point, the blind

turn not revealing until the last minute that the

road was flooded on the other side. But we

ploughed on, reaching a farm. A sign indicated

that All Saints Church was across the farmyard,

so we drove in. But the track on the other side

was a swamp, so the very kind lady at the farm

let us leave our car in the farmyard.

We walked along the track between wild hedgerows

and wooden palings, and eventually found

ourselves headed towards a handsome lychgate, the

tower and 19th century lantern of All Saints

peeping up above the wilderness of holly, ivy and

yew that surrounded it. Stepping through, we

found ourselves in the most delightful of

graveyards, with scatterings and groupings of

19th century graves among the wild trees; only

the modern graves to the east are organised in

rows. To the east of the church stands a massive

pine tree. This is unusual in Suffolk, where open

churchyards are more the rule these days, and it

places the building in a setting at once

dignified and mysterious, as if nature hadn't

entirely given this place up to the material

world.

My one disappointment of the day followed, for

the church was locked without a keyholder.

Mortlock tells me that much survives of the 14th

century, but that what appears to be a most

curious north chancel chapel is, in fact, a 17th

century vestry, built on two storeys. Looking

through the window, I could see that the

Victorians rather ingeniously knocked the floor

out, and opened the whole thing out into the

chancel. It is now an organ chamber, with the

character of a north transept, as at Baylham. The

19th century windows can be seen through the

clear glass of the north side, where I could also

just make out a 15th Century roundel of an angel.

But the churchyard was worth the visit alone.

Here, a strong sense of 19th century

sentimentalism has survived, of that

almost-Catholic piety nurtured by the Oxford

Movement, and then transmuted into emotion by the

sense of destiny of a National Church in

possession. The First World War would overcome

the silliness, and the end of Empire defeat it

all utterly. But that was still in the future.

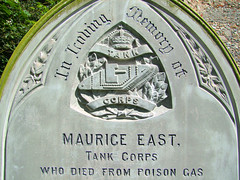

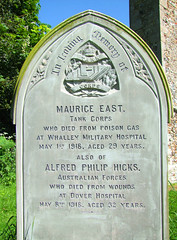

Death has haunted this little parish. Mortlock

reminds us that it was the first place in Suffolk

to report the Black Death (being, as it is, on

the Essex border) and at least 60 people died; 21

families with land lost all their adults. Here

also, the Danes and the Saxons fought a brutal,

bloody battle. The Parish lost two soldiers in

the First World War, and their joint gravestone

is one of the most explicit I've seen, rather

more moving than the sanitised official ones to

the east of it.

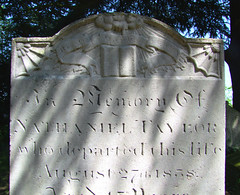

Another very striking feature of the churchyard

was the large number of cast iron gravemarkers.

Many of these are of a broadly similar design,

and cast at the foundry of W. I. Green, at

Sudbury. His nameplate is on the back of several,

and a pair leaning face down display it

prominently. Others are rather more ornate, with

a classical motif of a weeping woman by an urn,

and pious sentiments. I could find no foundry

name on these, but they probably came from the

Melford foundry which specialised in elaborate

memorials.

Most movingly, one of the cast iron markers, to a

child who died at the age of 2 in 1906, still had

fresh flowers before it. I found this again and

again in the graveyard; this is a well-loved,

well used place. On other entries I have been

disparaging about the recreational grave-tending

of the modern cult of the dead; family graves

seem to have taken over from allotments as a

place you make yourself busy, and churches that

were once considered places of private prayer

have been left behind long ago, their doors

locked and untried. But here, there was still a

sense of holy communion between the living and

the dead. But why are there so many 19th century

graves here? Can this parish really have been so

big 150 years ago?

< <

White's Suffolk 1844

records George Mumford at Caustons Hall and

George King at Peacock Hall. William Sandle, John

Bell, Henry Segers and Ann Taylor were four other

farmers. Edmund Tricker was a brickmaker, William

Rayner a blacksmith. William Pochin was Rector,

and that was about it as far as people important

enough to be named go. But 396 people lived here,

scattered across the parish, almost entirely

working on the land, making it a small to medium

sized parish for the time. The population is

about half that today.

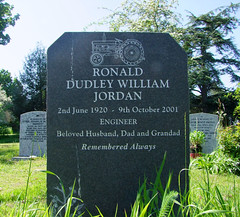

If rural populations are declining, it is despite

the efforts of the Knight family. Their modern

grave (mum died only in 1995) is to the east of

the chancel, and the back of it records no less

than SIXTEEN children born to the couple between

1934 and 1957.

And yet, what will remain with me is the

loneliness, the silence of that beautiful spot.

We walked back to the farmyard, wrapped up

against the sub-zero wind, wishing the similarly

wrapped up Nancy and her Mum a good morning along

the path. We drove back down to civilisation,

again being thankful for not meeting another car

on the narrow lane. Modern Sudbury engulfed us

with its noise, but we carried with us the

serenity of lonely Little Cornard. And so it was,

that evening, as I sat happily making a fool of

myself in the Ship and Star over pretty young

things, that I drifted away from the heat and the

noise occasionally, my mind picking its way

between the cast iron graves. I would go back

there.

Well, the years passed. The Ship and Star closed

and was converted into a house. I lost contact

with Catherine and Nancy. And so it wasn't until

the early summer of 2012 that I retraced my

footsteps, in the company of David Striker my

amazing American friend who has visited just

about every church in Norfolk, Suffolk and

Cambridgeshire despite the slight handicap of

living in Colorado City. It was a gorgeous day.

Twelve years had passed, and in any case the

churchyard looked so different under its cloak of

green and white that I remembered nothing. A

jolly bearded chap was exploring the churchyard -

you can just make him out in the photograph at

the top - and it was a reminder to me that a

number of footpaths meet here, this is a popular

spot for ramblers.

There was still no

keyholder notice, but there was a list of

the churchwardens which gave telephone

numbers. I rang one of them. He wasn't

terribly patient with me - he made it

clear he considered it an imposition for

me to call him. But he said if we were

prepared to wait he'd be there in fifteen

minutes.

Well, fifteen minutes became twenty, and

then twenty became thirty. As lovely as

this place was, there was no way we could

allow this amount of time on one church

when David had travelled from the States

for this trip. So, we left. We headed on

down the narrow lanes and

eventually reached the small town of

Bures beside the River Stour. Here we

stopped at a pub for a pint, sitting in

the garden in the sunshine.

After a while, my mobile phone rang. I

looked down at it, recognising the number

of the Little Cornard churchwarden. It

was almost an hour now since I had spoken

to him. Perhaps he was ringing me up to

apologise for being so late. Maybe

something awful had happened, maybe he'd

fallen down or had an accident or been

prevented in some other way from coming

to the church. But remembering how irate

he'd been when I rang him in the first

place I thought that this was probably

not the case, and so I didn't answer it.

|

|

|

|

|

|