| |

|

It is the remote and

hidden churches that entice me the most, and

Little Wenham church sits more than half a mile

from the nearest road. You reach it by a dirt

track which turns off by the Queens Head pub, and

then meanders through farm buildings and fields

before entering a curious fen-like area, over

which it is a causeway. You do not need much

imagination to detect the remains of a lost

settlement here. At last, it opens out into what

was clearly once an ancient farmyard, with the

church high on its mound to the east.

This churchyard is one of Suffolk's secret

places. The tower, its top repaired in red brick,

stands high above the nave and churchyard. The

porch itself is a little 15th Century wooden

structure, although it does have two unusual

features. Above the entrance, three image niches

are set in the wood, in a way familiar from stone

ones found elsewhere in Suffolk. Also, the

entrance contains slots for a drop-bar gate,

existing elsewhere in Suffolk at Badley, a

similarly remote church. Its purpose was probably

to keep animals out.

But we are able to step inside. This is one of

those churches which thrills with its

idiosyncratic character and richness of interest.

The remains of the medieval stone rood screen,

existing elsewhere in Suffolk only at Bramford,

lead you through to the chancel, where you stand

before some of the loveliest wall paintings

in all Suffolk. Because the church was

built pretty much all of a piece in the middle of

the 13th Century, and because the original early

Decorated east window is still in place, it is

safe to assume that these wall paintings are the

original decorations, painted for the building's

consecration when it was first built.

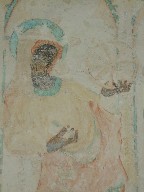

To the south of the window are saints Margaret,

Catherine and Mary Magdalene. To the north, the

Blessed Virgin and child, flanked by angels. The

most striking thing about these beautiful flowing

figures is that the centuries have oxidised their

skin tones quite black. They are exquisite.

And, as if that were not

enough, the chancel also contains one of

Suffolk's best pre-Reformation pairs of figure

brasses. Thomas Brewse of little Wenham Hall, who

died in 1514 and his wife Elizabeth lie before

the altar, stately and proud, confident in their

position and in the perpetuity in which Masses

would be said for their souls. In fact, those

Masses would last barely thirty years.

Interestingly, someone at some point has

attempted to scratch out the rose shapes on

Elizabeth's girdle. Perhaps they thought it was a

rosary. Beneath them, their children stand, boys

to the left, girls to the right. The girls have

long, flowing hair, showing that they were

unmarried at the time of their father's death.

The Reformation would result in a different kind

of memorial, where civil power could be

legitimately expressed. The Brewses held the hall

into the 18th Century, and were patrons of this

church. Either side of the altar are two other

memorials to them. To the south is John Brewse,

who died in 1585. He is in good condition, and

finely crafted. He kneels at prayer, a different

kind of piety to that of his great grandfather on

the chancel floor. He looks as if he might get up

and walk away at any moment. To the north of the

altar, what was plainly an Easter Sepulchre, a

pre-Reformation tomb for another member of the

Brewse family (it bears an earlier form of the

shield across the chancel) but for which one is

now unknown. However, in 1785 it was

pragmatically reused for John Brewse, a

descendant of the other Brewses in the chancel.

This is a church it's hard

to resist returning to as if it were an old

friend. And yet, it almost didn't survive for us

to see it. In the late 19th Century it was quite

derelict, and a decision was taken to demolish

it. At the meeting held to discuss this, it is

said that the sexton swayed opinion by stating

that "the old girl's been around such a long

time, it seems a shame that she should fall down

now." His eloquence led to its restoration,

and a photograph of this hero can be seen to this

day, beneath the tower arch.

|

|

|