| |

|

|

|

Saxmundham is a fine

little town more or less halfway between Ipswich

and Lowestoft. Saxmundham, or 'Sax' as locals

call it, grew to prominence in the 18th and 19th

centuries, and it still retains something of that

period's character. But it is not a tourist town,

unlike its rival Framlingham, or 'Fram', just

across the A12. The

Waitrose and Tesco superstores, which the locals

fought long and hard against because of the

effect they would have on local shops, are set

sensitively just off the high street, which still

retains some interesting shops, though none of

them sell food of course. And the other thing

missing, although this can't be blamed on the

superstores, is a dominating medieval church,

because St John the Baptist is away from the main

street on the road to Leiston.

The church sits up on a hill, his

higgledy-piggledy churchyard falling away on all

sides and full of interest. The headstones of

18th and 19th century worthies point to the

wealth of the town in the past. Most famous is

the headstone to John Noller, which has its own

sundial.

|

There is a crisp 19th century feel

to the church in this sea of headstones. It was subject

to an 1870s restoration at the hands of Diocesan

architect Richard Phipson. However, Phipson was more

sensitive to the need to preserve medieval survivals than

his successor Herbert Green, and so the church is also

full of interest. More recently, at the start of the 21st

Century, there has been a splendid reordering and

restoration of the nave, and so you step into wooden

floors and modern chairs set sparingly in the light. I

had remembered this as rather a gloomy space, and so

coming back in early 2018 I was pleased and surprised.

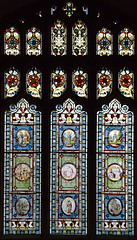

The simplicity and sensitiveness of

the modern reordering allows the 19th Century windows to

be a feature, and they are all good of their kind. Most

are to members of the Long family of Hurts Hall. In the

south chancel aisle, the former Swans Chapel now set

aside for prayer, is Harry Ellis Wooldridge's window of

1875 for Powell & Sons depicting the Sermon on the

Mount, full of character and interest in an early Arts

and Crafts style. Dominating the west end of the south

aisle is a vivid depiction of the Ascension made by the

O'Connor workshop after George Taylor had taken over as

its boss. It is believed to have been designed by the

Pre-Raphaelite artist Louisa Beresford. The setting of

the new kitchen area beneath it is slightly surreal,

though not unsuccessful.

The most interesting glass is in the east window of the

south chancel aisle. Here, Powell & Sons reset a

collection of 17th Century roundels and ovals, including

a hermit representing one of the four seasons, the Holy

Kinship of St Anne, the Blessed Virgin and the infant

Christ, as well as other Saints, the Prodigal Son and

scenes of the Works of Mercy.

The font, though considerably

recut, is one of the best Suffolk examples of the 15th

century East Anglian style. There are feisty little wild

men around the base, and one of the shields features the

instruments of the passion. Another medieval survival

here, and a rare one, can be seen in the most easterly

windows of each of the clerestories. This is a pair of

stone corbel ledges that once supported the canopy of

honour over the rood. They are both carved elaborately,

and the northern one is castellated. The inscription on

the southern side reads Sancta Johnannes, Ora Pro

Nobis ('St John pray for us').

When the antiquarian David Elisha

Davy visited the church on Thursday 21st August 1834, he

was rather overwhelmed by what he found. This was, of

course, before Phipson's restoration and the installation

of the present stained glass windows. Rather, Davy got

bogged down with memorials to, and records of, the Long

family, and ran out of time, because the carriage he was

travelling by was only stopping in the town for two hours

on its way from Yoxford to Ufford, while the horse

was baited. I found so much that I was obliged to leave a

part undone, Davy complained, and Mrs Long's

death which took place the evening before will, probably,

add somewhat to the novelties which I shall find on my

next visit.

| Saxmundham was unusual for

a town in that it was almost entirely contained

in one manor, Hurts, the domain for centuries of

the Long family. One small part of the town was a

separate manor, Swans, and this gave its name to

the south aisle chapel of the church. In the

early 19th Century, Swans was in the ownership of

Dudley Long North, whose grand and slightly

alarming effigy can be seen in the North

mausoleum down the road at Little Glemham. At the time of the 1851 census of

religious worship, Saxmundham had a population of

just under 1200, some 200 of whom tipped up for

morning worship on the morning of the census.

This compared favourably with a similar number

turning up that morning at the independent

chapel, because in most East Anglian towns the

non-conformists greatly outnumbered the adherents

to the established church. Even so, Robert Mann,

the minister of St John the Baptist, was

sensitive about the size of his congregation and

felt the need to explain it. In common with many

of his colleagues across Suffolk, he made an

excuse for the poor attendance when he filled in

the census return. Uniquely in the county, he put

the blame on the absence of children, many of

whom are suffering from hooping cough.

Saxmundham church would, I am sure, need to make

no such excuses today. It feels a lively place,

at once mindful of its past and fitting for its

present.

|

|

|

Simon

Knott, April 2018

|

|

|